Researchers have demonstrated a new method for producing clean hydrogen from water using sunlight and liquid gallium, opening a potential new pathway for scalable green hydrogen production without the constraints of conventional electrolysis.

The technique, developed by a research team led by the University of Sydney and published in Nature Communications, uses the natural chemical behaviour of liquid metals to extract hydrogen from both freshwater and seawater, avoiding the need for purified water or energy-intensive processing.

Hydrogen is widely viewed as a critical component of future low-carbon energy systems, particularly for sectors such as heavy industry, shipping and long-duration energy storage. However, producing hydrogen in a way that is both economically viable and genuinely low-emissions remains a major challenge.

Liquid metals offer a different route to green hydrogen

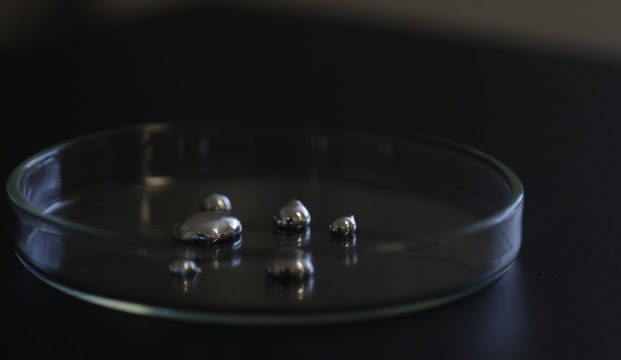

At the centre of the new process is gallium, a metal with a low melting point that becomes liquid at near-room temperature. When suspended as fine particles in water and exposed to sunlight, liquid gallium reacts at its surface, releasing hydrogen while forming gallium oxyhydroxide.

Lead author and PhD researcher Luis Campos said the approach allows hydrogen to be extracted using readily available water sources and light alone.

“We now have a way of extracting sustainable hydrogen using seawater, which is easily accessible, while relying solely on light for green hydrogen production,” Campos said.

Crucially, the process is circular. After hydrogen is released, the gallium oxyhydroxide can be chemically converted back into liquid gallium and reused, reducing material losses and improving long-term sustainability.

Competitive efficiency at an early stage

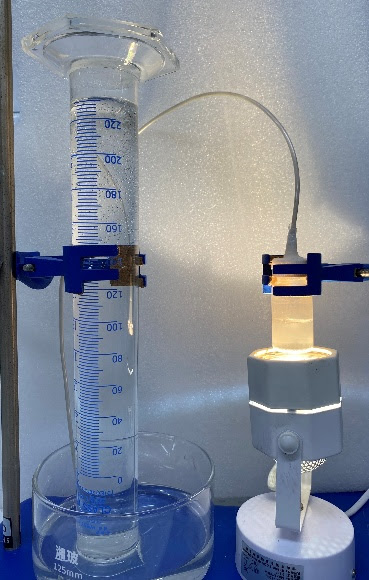

Researchers used liquid gallium and light to extract hydrogen from water in a laboratory proof-of-concept.

The research team reported a maximum hydrogen production efficiency of 12.9%, which they describe as competitive for an early proof-of-concept system.

Senior researcher Professor Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh, from the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, noted that many now-mainstream clean technologies began with similar or lower efficiencies.

“Silicon-based solar cells started with around six percent efficiency in the 1950s and did not pass 10 percent until the 1990s,” he said. “For a first demonstration, this technology is highly competitive.”

The team is now focused on improving efficiency further and developing a mid-scale reactor to test the technology beyond laboratory conditions.

Overcoming long-standing barriers in hydrogen production

Most current green hydrogen production relies on electrolysis, which requires large amounts of electricity, high-purity water and expensive infrastructure. Other experimental approaches, such as photocatalysis or plasma-based methods, have struggled with low yields or high costs.

The liquid gallium approach avoids several of these bottlenecks. It can operate with seawater, does not require electrical input beyond light exposure, and relies on a material that can be reused repeatedly within the system.

Researchers say gallium’s behaviour in water under light exposure had been largely overlooked until now.

“Gallium has not been explored before as a way to produce hydrogen at high rates when in contact with water,” Professor Kalantar-Zadeh said. “It’s a simple observation that was ignored previously.”

Implications for the hydrogen economy

Hydrogen is increasingly viewed as a strategic energy vector, particularly for countries seeking to decarbonise energy-intensive sectors and develop export-oriented clean fuel industries. Project co-lead Dr François Allioux said advances like this could strengthen Australia’s position in a future hydrogen economy.

While the technology remains at an early stage, researchers argue that its simplicity, circular chemistry and ability to use non-purified water make it a promising candidate for further development.

As governments and industries search for scalable, low-cost routes to green hydrogen, alternative production pathways such as liquid metal-driven reactions could play a growing role alongside electrolysis in the global energy transition.